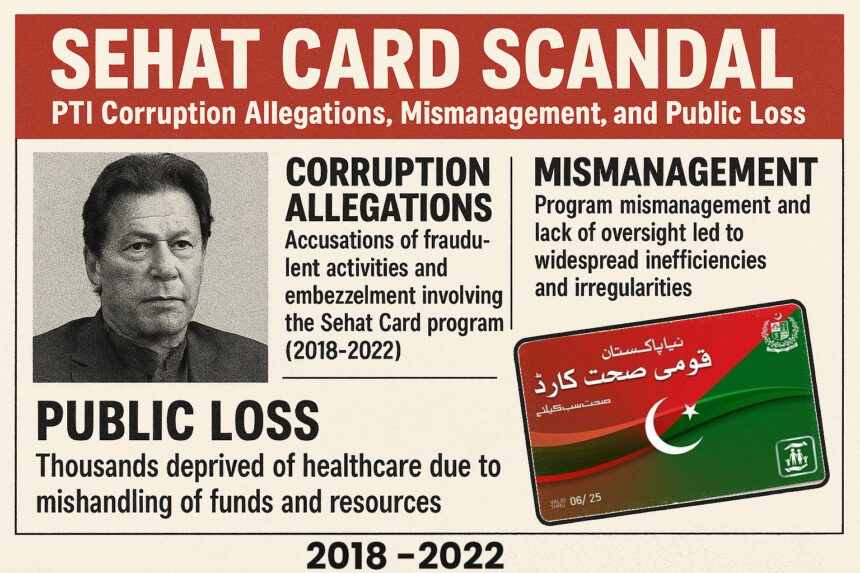

Sehat Card Scandal: PTI Corruption Allegations, Mismanagement, and Public Loss (2018–2022)

The Sehat Card program, launched with the promise of free, universal health coverage, became one of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government’s flagship welfare initiatives. Between August 2018 and April 2022, it expanded nationwide, offering each family coverage of up to Rs. 1 million for medical treatment.

However, official audits and investigative reports later revealed deep flaws—mismanagement, weak oversight, and corruption allegations. The heaviest losses were recorded in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), PTI’s political stronghold, where the Auditor General of Pakistan (AGP) found more than Rs. 28.61 billion in financial irregularities.

(August 2018 – April 2022) — Sehat Card Record and Corruption-Related Concerns

During PTI’s rule from August 2018 to April 2022, there were major issues of fund misuse and suspected corruption in the Sehat Card program. Most irregularities were reported in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), where PTI was in power. According to the Auditor General of Pakistan (AGP), over Rs. 28.61 billion in financial irregularities were found in the health department, including the Sehat Card scheme. These issues arose from poor management, violations of rules, and possible corruption. Based on official audit reports and credible news sources, here is an easy-to-follow explanation of how this happened.

Corruption Reports and Allegations

1. Excessive Surgeries and C-Sections in Punjab

In Punjab, after PTI expanded the Sehat Sahulat Card program in 2019, significant issues arose, particularly with private hospitals. Total payments for C-Sections under the program reached Rs. 16.36 billion, with nearly 80% of the 525,619 procedures conducted in private hospitals, including Rs. 8.16 billion in 2022 alone. Many of these C-Sections were medically unnecessary, driven by profit motives, which harmed patients and misused taxpayer money. These issues highlight a significant diversion of public funds to private healthcare providers, with weak oversight contributing to corruption and inefficiencies.

Sources: Khyber News, Dawn, The Express Tribune

2. Over-Treatment and Fraud

Some private hospitals exploited the program by performing up to 48 surgeries in a single day, conducting unnecessary C-Sections, and adding extra treatments for multiple patients. One private hospital billed Rs. 900 million for treatment of specific diseases—an amount later ignored by regulators. (Sources: Arab News, Business Recorder, Dawn)

3. Referrals from Public to Private Hospitals

Many public hospitals directly referred patients to private facilities, reportedly in exchange for financial incentives. On average, out of 1,500 patients each month, around 300 were shifted to private hospitals. (Source: The Express Tribune)

4. Investigations and Political Response

In March 2024, Punjab’s finance minister announced an investigation into alleged corruption in the Sehat Card program. (Sources: Arab News, Business Recorder, Dawn)

5. Financial Irregularities in KP

The AGP’s report revealed shocking figures—over Rs. 28.61 billion in financial irregularities in KP’s Sehat Insaf Card program. (Sources: Wikipedia, Facebook, Instagram)

6. Inquiry into Taimur Jhagra

KP Health Minister Taimur Jhagra faced allegations of corruption linked to the Sehat Card program, procurement of medical equipment, and COVID-19 relief funds. (Source: Khyber News)

Global or International Comparison — Similarities and Differences

Internationally, while there have been corruption cases in health insurance or cashless health card systems, no scandal has been documented on the same scale and intensity as in Pakistan.

Universal health coverage and government-funded health insurance face fraud and irregularity risks worldwide:

-

India (Ayushman Bharat PM-JAY): Over 1,100 hospitals removed and 1,500+ fined for fraudulent claims. (Source: Medical Dialogues)

-

Philippines (PhilHealth): 2020–2024 saw major corruption allegations, legislative inquiries, and fake claims controversies. (Sources: Devex, Inquirer.net)

-

Mexico (Seguro Popular, 2003–2019): Billions in irregularities and ghost payments, eventually replaced by INSABI. (Sources: Mexico News Daily, BNamericas)

-

Indonesia (JKN): Research documented billing for unperformed services, unnecessary tests/treatments, and kickbacks. (Source: CMI – Chr. Michelsen Institute)

Fraud risk is a recognized global challenge in government-funded health insurance. Solutions combine data analytics, strict hospital credentialing, biometric/digital auditing, and swift punitive action—gaps that were especially evident in Pakistan.

Program Launch and Expansion

-

Federal Expansion: After starting in KP in 2015, PTI’s federal government expanded the “Sehat Insaf Card” nationwide on February 4, 2019.

-

Punjab Launch: In December 2021, Prime Minister Imran Khan launched the “Sehat Card” program in Punjab, making it available in almost the entire country, offering up to Rs. 1 million per family for treatment.

Administrative Weaknesses and Poor Monitoring

Vacant Key Posts: In Punjab, the Sehat Card team (PHIIMC) had the positions of CEO and COO vacant for two years, with operations running on an ad-hoc basis. This led to inconsistency and susceptibility to influence.

Transparency and Alleged Figures

On social media and in public discussions, allegations were made of around Rs. 10 billion in corruption. However, no conclusive and officially verified government report exists to confirm this—these remain unverified claims.

When monitoring is weak and incentives are misaligned, welfare programs turn into profit-making opportunities. The burden of such misuse eventually falls on citizens in the form of higher taxes, inflation, and public debt.

Impact on the Public

The cost is not only financial but also human:

-

Unnecessary medical procedures (e.g., repeated C-Sections instead of normal deliveries).

-

Use of substandard or harmful medical practices (e.g., Avastin case—contaminated injections causing loss of eyesight in dozens of patients).

Such patterns intensify when private-sector participation is high and public oversight is weak. In KP’s 2021 data, 69% of patients went to private hospitals and 31% to public hospitals, with per-patient costs significantly higher in private facilities. (Source: AGP report)

AGP Findings — Rs. 28 Billion+ Irregularities in KP Health Card

In August 2025, the AGP report revealed that between 2017–18 and 2021–22, the KP Health Card and health sector faced over Rs. 28 billion in irregularities, including payments to 17 unregistered hospitals and weak tax deductions. (Government/department responses are reportedly in process.)

Where the System Failed — Key Cases and Figures

-

Unusual Shift Towards C-Sections in Punjab

Dawn reported that between 2018–2022, a very high share of deliveries under the program were C-Sections—197,376 compared to 97,390 normal deliveries—mostly in private hospitals, raising concerns of financial incentives driving unnecessary surgeries. -

Fraudulent/Incorrect Claims and Unnecessary Admissions

The Express Tribune (2023) documented tactics such as fake admissions, unnecessary surgeries, and inflated billing—the more the claims, the higher the payments.

Breakdown of Key Irregularities

| Problem | Details | Amount Involved | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Payments to unregistered hospitals | Hospitals not approved by Health Care Commission still received payments, violating the State Life Insurance agreement. | Over Rs. 2 billion for two hospitals | Anwar Hospital & Kings International Hospital in Swat got Rs. 1.028 billion each without registration. |

| No tax deduction | Govt paid State Life without deducting 8% income tax. | Rs. 2.16 billion loss | Full payment made without tax cuts from 2017–2022. |

| Extra hiring without need | Overstaffing in 32 district hospitals without justification. | Rs. 824 million | Wasted on excess cleaning/security staff. |

| Breaking procurement rules | Contracts awarded without open tendering, violating KP’s KPPRA rules. | Rs. 198 million | One company received all contracts without competition. |

| Advance payment without work | Funds given for hospital repairs, but work never started. | Rs. 1.072 billion | Paid to Punjab’s Infrastructure Development Authority; no progress by April 2023. |

| Overcharging by private hospitals | Private hospitals treated fewer patients but charged far more. | Rs. 882.7 million in one case | Sardar Khan Private Hospital (14,999 patients) vs. Bacha Khan Complex (29,911 patients at Rs. 338.2 million). |

Consequences — Rising National Debt

Poor economic policies or corruption (like the Sehat Sahulat Card issues) can worsen the debt burden, as public funds are misused instead of being used productively. International lenders may impose strict conditions (e.g., IMF reforms), which can lead to austerity measures, affecting the public through higher costs or fewer services.

Rising debt can lead to inflation, higher prices, and a weaker rupee, reducing people’s purchasing power. For example, the exchange rate jumped from Rs. 105 per dollar in 2017 to around Rs. 200 by 2022, making imports (like fuel and food) more expensive for everyone.

In short, the debt is ultimately paid by Pakistani citizens through taxes, reduced services, and economic pressures, with the burden potentially lasting for decades if not managed well. If you want more details or a specific aspect explained, let me know!

Question

Who Pays the Debt?

Answer : You & Your Future Generation

One major outcome was the increase in Pakistan’s per capita debt:

-

2017: $1,027 (~Rs. 108,000) per person.

-

April 2022 (June 2022 data): $1,277 (~Rs. 216,709 to Rs. 256,000) per person.