The murder that foretold a war

It did not start in a vacuum. In the years leading to November 1980, Pakistan’s sectarian temperature rose through pulpit wars and procession disputes. In multiple towns, specific majlis sermons by some zakireen were widely heard as toheen-e-sahaba (insult to the Companions)—not just rumors but often documented in FIRs and, in some cases, convictions under PPC 295-A/298-A. Street protests, counter-speeches, and tense Muharram routes followed. When the Iranian Revolution energized Shia politics, On 3 November 1980, in Lahore’s Islām Pura, the Shia khatib Syed Muhammad Jafar Zaidi was killed at his doorstep with hammer blows; he was accused of spreading toheen-e-sahaba (insult to the Companions). In contemporary memory, that murder is often treated as the first spectacular crack in a long, bloody fissure that widened across Pakistan through the 1980s and 1990s. Over the next two decades, sectarian assassinations, pogrom-like riots, proxy contests, and insurgent spin-offs would transform routine theological disagreements into an entrenched, militarized conflict touching nearly every province.

Why did a country whose public life long carried Sufi inflections and Sunni–Shia coexistence tip into organized sectarian violence? Three shocks—and the policies they catalyzed—shaped the answer: Iran’s 1979 revolution, the anti-Soviet Afghan war, and General Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamization program.

Long roots, shallow politics

Doctrinal differentiation between Sunni and Shia Islam is ancient, but for much of the 20th century in Pakistan, friction was bounded. Muharram tensions flared episodically and then receded. Sunnis often joined Shia rituals out of civic solidarity; intermarriage existed; and the shared civic order generally contained differences. That changed at the turn of the 1980s as geopolitics, ideology, and statecraft fused.

The triple shock

1) The Iranian Revolution (1979)

The Islamic Revolution electrified Shia communities globally, including Pakistan—home to one of the world’s largest Shia populations outside Iran. Tehran’s cultural outposts (Khanah-e-Farhang), films, pamphlets, and scholarships to seminaries in Qom and Mashhad carried a new lexicon of political Shiism: vilayat-e-faqih, jihad, resistance. Returning Pakistani students brought back both learning and revolutionary zeal—and increasingly contested older, quietist religious leadership.

2) The Afghan Jihad (1979–1989)

The Soviet invasion turned Pakistan into the rear base of a global insurgency. Money and weapons surged in. Refugees and fighters flowed across the Durand Line. Deobandi and Ahl-e-Hadith networks, tight with Afghan mujahideen, expanded rapidly. The jihad normalized weapons, militant training, and clandestine logistics—capacities that later migrated into sectarian outfits. Arms proliferated; police and clerics alike began seeking weapon licenses; public rallies became theatres of gun displays.

3) Zia’s Islamization (1977–1988)

After deposing Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, General Zia promised quick elections, then entrenched himself by adopting an Islamization agenda aligned with Sunni jurisprudence. For Shias, the most incendiary measure was the 1980 Zakat and Ushr Ordinance, which—being based on Hanafi fiqh—clashed with Jafari jurisprudence on collection and distribution.

In July 1980, an anti-Ordinance sit-in in Islamabad swelled to well over a hundred thousand Shias under the banner of the newly assertive Tehrik-e-Nifaz-e-Fiqh-e-Jafaria (TNFJ). Clashes with police left at least one protester dead from a tear-gas canister strike. The sit-in—framed by leaders as a “Karbala of July heat and dry water”—forced Zia to exempt Shias from state-collected zakat. Though hailed as a Shia victory, it hardened perceptions: Sunni hardliners saw state capitulation; Shias saw proof that mobilization worked. The sectarian chessboard was set.

The proxy overlay: Riyadh and Tehran

As Iranian influence grew through cultural diplomacy and clerical education, Saudi Arabia scaled up support to Deobandi and Ahl-e-Hadith seminaries and charities. Funding, book distribution, and madrasa construction accelerated. Competing patrons deepened doctrinal polemics and organizational capacity. From the Pakistani street, the conflict increasingly looked like a Saudi–Iran proxy filtered through local histories.

From rhetoric to rifles: arenas of early violence

Kurram Agency (Parachinar)

Kurram’s Turi tribe (predominantly Shia) abutted Sunni Pashtun tribes and the Afghan front. By the mid-1980s, as arms sluiced in, skirmishes mutated into sieges. In July 1987, Sunni tribal coalitions and Afghan fighters reportedly mounted large offensives; both sides fielded militias, and casualties ran into the hundreds.

Gilgit, 1988

Eid moon-sighting discrepancies triggered riots; then rumors metastasized into mass violence against Shias in parts of Gilgit. Contemporary Shia narratives alleged that a lashkar including Afghan mujahideen and militants linked to Osama bin Laden traversed the Karakoram Highway and participated in massacres and village burnings. The allegation remains contested; what is uncontested is that the security state failed to prevent a devastating pogrom.

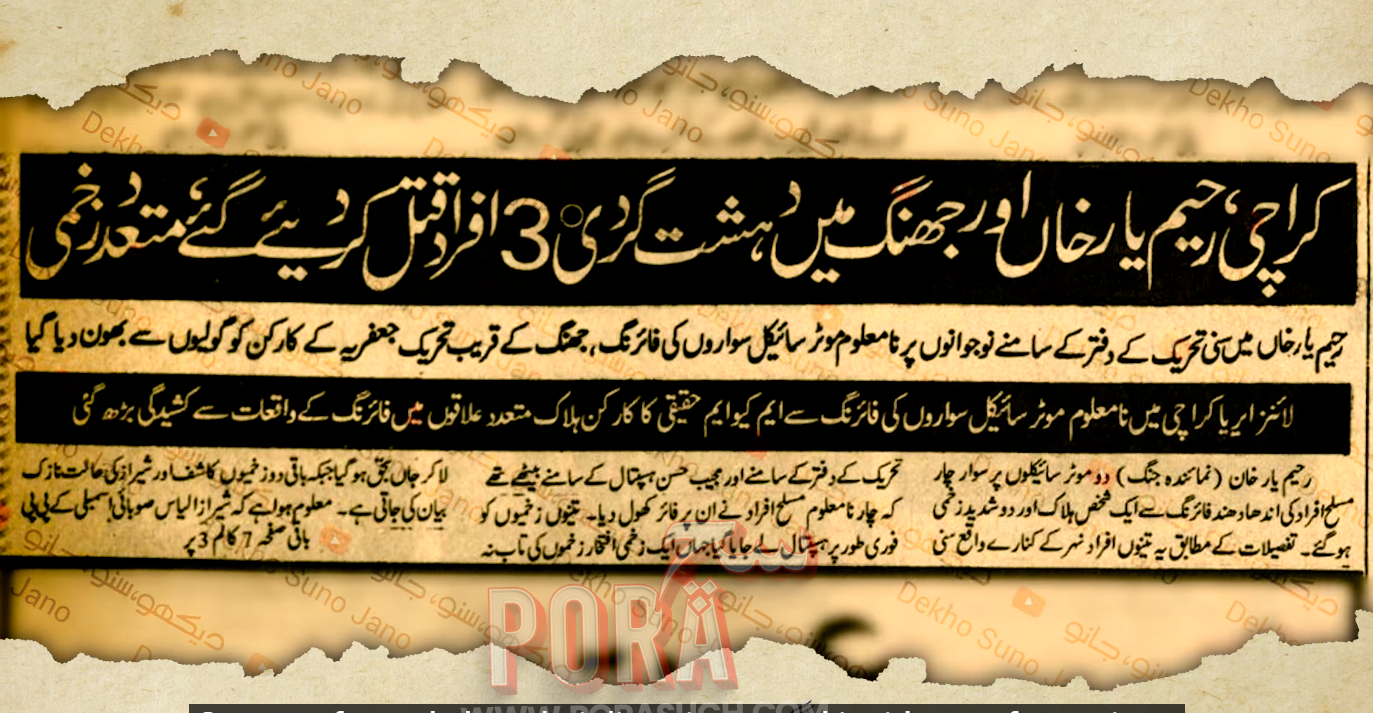

The urbanization of sectarianism: Lahore, Karachi—and Jhang

Lahore and Karachi

By the mid-1980s, Muharram processions in Lahore and contests over mosque control in Karachi had turned into flashpoints. Attacks on Iranian cultural targets in the late 1990s (arson in Lahore; killings in Multan and Rawalpindi) signaled a new, dangerous horizon—sectarian violence now intersected with regional diplomacy.

Jhang: a case study in structural change

Jhang—once woven through with Sufi memory, romance epics, and Barelvi-leaning Sunni practice—underwent convulsive change after Partition as Deobandi-leaning muhajirs from Panipat/Hisar/Gurgaon/Rohtak settled in. Over time, agrarian hierarchies (often Shia landlords in the rural periphery) and a rising urban mercantile Deobandi class rubbed against each other. Sermon wars escalated (e.g., the 1969 “Khoo-wa Gate” incident over signage during Muharram). Loudspeaker polemics and counter-polemics normalized humiliation as a tactic.

In 1985, the charismatic but hardline Jhang cleric Maulana Haq Nawaz Jhangvi founded Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP), organized around three maximalist aims: declare Shias non-Muslim, ban Muharram processions, and remake Pakistan as a Sunni state. Stickers, wall-chalking, and packed “Sahaba Conferences” spread a simplified message: anti-Shia politics as religious duty. Jhangvi’s assassination on 22 February 1990 unleashed days of rioting; revenge killings and pogroms would now alternate with elections.

Shia mobilization and counter-mobilization

TNFJ/Tehrik-e-Jafaria and Arif Hussain al-Hussaini

Under Allama Arif Hussain al-Hussaini (assassinated August 1988), Shia politics grew more mass-based and youth-oriented. The Imamia Students Organization (ISO) became a cadre nursery. Friday sermons adopted a sharper political idiom (“America murdābād” etc.), aligning transnationally while confronting domestic security policy. His murder—followed 11 days later by Zia’s fatal plane crash—remains a turning point in Shia political memory.

Paramilitarization: Mukhtar Force → Sipah-e-Muhammad Pakistan (SMP)

As target killings mounted, Shia actors experimented with protection units—Mukhtar Force, Al-Badar—and eventually, in the early–mid 1990s, the clandestine Sipah-e-Muhammad Pakistan (SMP). Figures associated with Qom tutelage and Afghanistan battlefields surfaced as organizers. SMP adopted a mirror-image repertoire—ambushes against SSP leaders and operatives—further accelerating tit-for-tat dynamics. State crackdowns, arrests, and later proscription (2001–2002) fractured the network; funding reportedly tightened after attacks that killed Iranian nationals.

From cadre party to terror franchise: Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ)

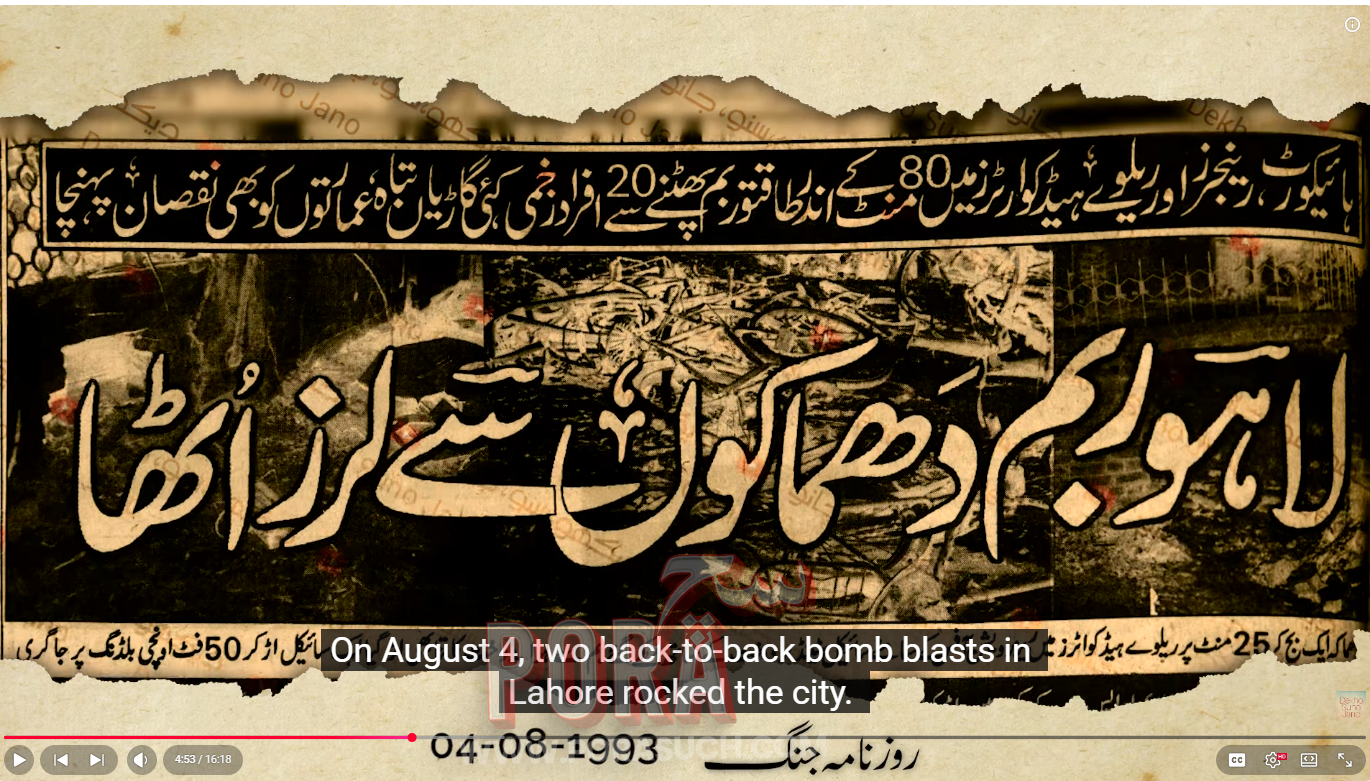

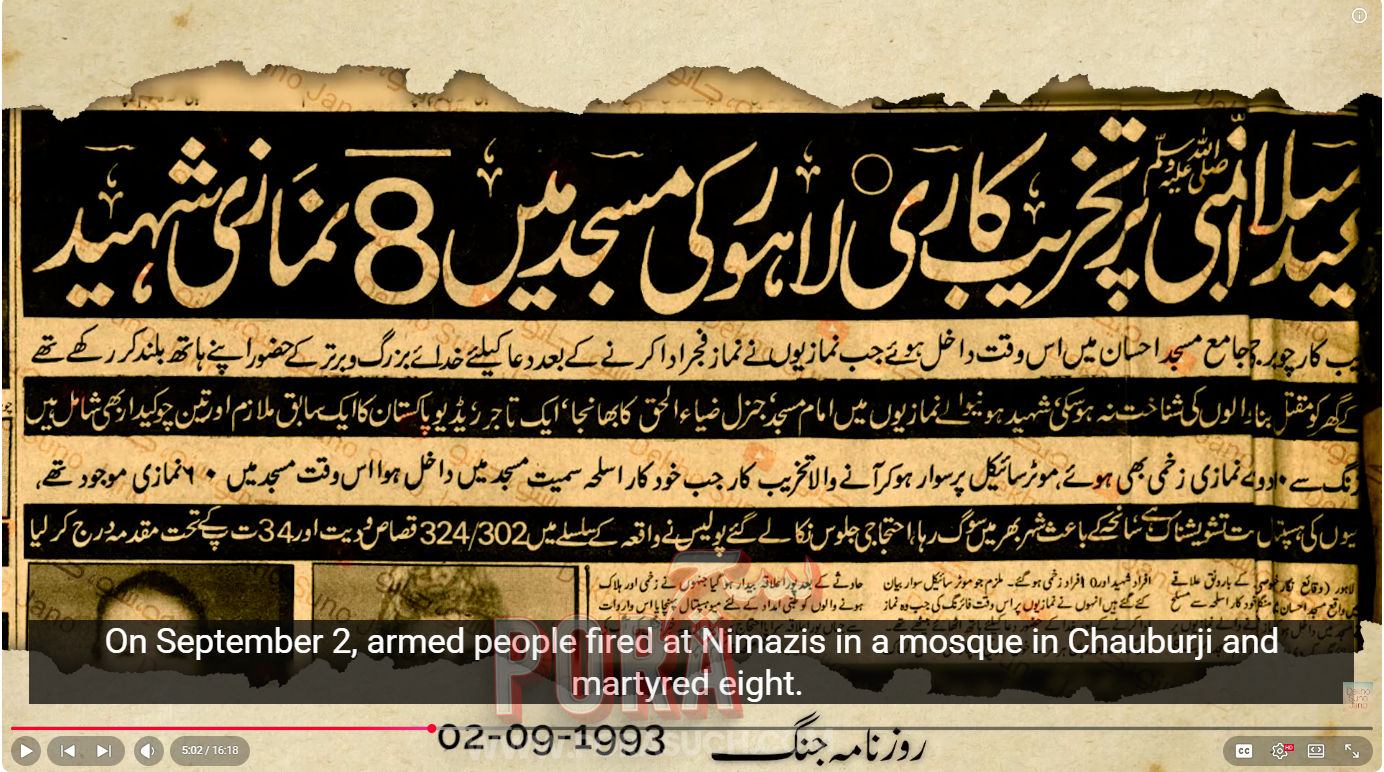

By the mid-1990s, a younger, more lethal cohort split from SSP to found Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ)—names like Riaz Basra, Malik Ishaq, Akram Lahori became shorthand for urban terror. LeJ pioneered mass-casualty operations alongside targeted assassinations—against Shia professionals (doctors, engineers, academics), processions, imambargahs, and Iranian targets. Claim calls to newsrooms became grimly routine. Over time, strands of LeJ meshed with regional jihadist networks; after 2001, portions plugged into al-Qaeda’s “313 Brigade,” while others remained domestically focused. Quetta’s Hazara Shias suffered especially horrific bombings (e.g., 2013’s January attacks with well over 100 dead).

State responses oscillated: special courts and encounter killings in Punjab (late 1990s), periodic mass arrests, and bans (2001–2002) on LeJ, SMP, SSP, and other jihadist outfits. Yet name-changes (e.g., SSP elements re-badged as Ahle Sunnat Wal Jamaat), political accommodations, and uneven prosecutions blunted deterrence. High-profile assassinations continued: SSP chief Zia-ur-Rehman Farooqi (killed 1997 in a court bombing), parliamentarian Maulana Azam Tariq (shot dead near Islamabad, 2003), and multiple retaliatory hits across Punjab and Karachi.

Techniques of violence and the political marketplace

Target sets: clerics, prayer leaders, procession marshals, doctors and lecturers (to magnify fear), Iranian diplomats and trainees, police investigators, and rival organization chiefs.

Tactics: motorcycle assassinations; IEDs under stages at rallies; car bombs; storming mosques with automatic weapons; synchronized blasts; and strategic public claims of responsibility.

Enablers: clandestine training pipelines (some overlapping with Kashmir-focused camps in Muzaffarabad or Balochistan), madrasa and student-group recruitment nodes, and criminal–militant symbioses.

Political shielding: sectarian leaders leveraged seats in assemblies, electoral bargaining, and street power to extract concessions or short-term releases; in turn, governments occasionally sought their votes or street discipline.

Why Jhang mattered symbolically

Jhang condensed the national story: agrarian class cleavages (often mapped onto sect), the post-Partition religious shift in urban demography, mosque pulpit wars, entrepreneurial clerical populism, and a ready pipeline of young men trained in Afghanistan. The 1991 assassination of Maulana Isar al-Qasmi, a key sectarian politician, and the subsequent militarized lockdowns showed how easily electoral politics could be drowned by gunfire.

A grim ledger—then a partial ebb

By the early 2000s, sectarian outfits had split, rebranded, or embedded in broader jihadist stacks. Proscriptions in 2001–2002 removed formal space but not capability. Policing in Punjab (late 1990s to mid-2010s) killed or captured multiple LeJ commanders; prisons cycled others. Yet bombings in Quetta and targeted killings in Karachi and the Punjab heartland recurred in waves. The long war’s “cold peace” periods masked unresolved drivers—patronage, impunity, and hardened social distance.

The cost: social fabric, state capacity, and foreign policy

-

Human capital: Hundreds of doctors, professors, and civil servants were murdered for identity alone. Communities retreated into ghettoized security.

-

Rule of law: Encounter justice and selective bans corroded institutions even as they saved lives in the short term.

-

Foreign relations: Attacks on Iranian targets repeatedly strained Islamabad–Tehran ties; accusations of cross-border meddling ran both ways.

-

Civic trust: Muharram—once both mourning and civic ceremony—became a signal of emergency law and city-wide shutdowns.

Lessons and unresolved questions

-

Geopolitics localizes: External patronage (Tehran/Riyadh) amplifies but does not create conflict; it grafts onto local grievances—class, demography, position in the state.

-

Militarization is sticky: Once clandestine training, logistics, and finance are established, they do not evaporate with a ban; they mutate.

-

Selective bargains backfire: Short-term political deals with sectarian actors tend to purchase quiet with long-term instability.

-

Narratives matter: Dehumanizing language from pulpits and pamphlets preceded bullets. Rolling back sectarian violence requires doctrinal de-escalation and cross-sect coalitions, not just kinetic policing.

Epilogue

From Islām Pura’s doorstep killing in 1980 to mass-casualty bombings in the 2010s, Pakistan’s sectarian wars were never just “Sunni vs Shia.” They were a convergence: of revolutionary aspiration and counter-revolutionary fear; of jihad’s logistics bleeding into city streets; of a state that Islamized law while struggling to monopolize force; and of local class politics weaponized by transnational agendas. The ledger is heavy. The path away from it runs through memory with moral clarity, law with evenness, and a politics that refuses to hire the gunman to win the argument.